Byzantine Mosaic Panel

Byzantine Mosaic Panel

Byzantine Empire

Circa Early 5th Century A.D., possibly Antioch or Apamene

Stone

H:79cm W:200cm

PoR

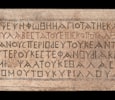

A rectangular Byzantine mosaic, comprising six lines of Greek text in black and red tesserae set within a blue rectangular frame against a white background. The second line down is in red, the rest in black. The inscription translates as: ‘In the year 727 [probably 415/416 A.D.] the most sacred church was paved with mosaics, under the most venerable bishop Alexander, under John the periodeutes, Antiochos the priest, Stephen the deacon, Benjamin the cantor, and Thalassios the steward of Cyril’. The text terminates with a stylised palm frond in black.

The art of the mosaic flourished throughout the Byzantine Empire (330-1453), building on Hellenistic and Roman practices with significant technical advances to transform the mosaic into a powerful form of personal and religious expression. The Byzantines expanded the range of materials that could be used as tesserae, adding gold leaf and precious stones to their more ornate designs. Before the tesserae were laid, the foundation was prepared in multiple layers. The final layer was formed of a fine mix of crushed lime and brick powder, like cement. While this surface was still wet, artists traced the outlines of the design into the surface, before carefully positioning the tesserae into the final image.

Two main types of mosaic survive from this period: wall mosaics in churches and palaces, made of glass tesserae against gold leaf, and floor mosaics crafted from stone. The vast majority of extant mosaics are of religious nature, and feature similar subjects to painted icons and manuscript miniatures from the time. These were never placed on the floor, as it was unacceptable to walk upon images of sacred figures. Floor mosaics often featured geometrical patterns and animals, as well as scenes of hunting and venatio. Based on the materials used for this aniconic panel, it is likely it was placed in the floor of the church it was dedicated to, as a record of the other mosaics installed around the walls.

Sheila McNally, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts Bulletin, LVIII (1969), p. 5, no. 1.

Pierre Canivet, ‘Nouvelles Inscriptions Grecques Chrétiennes à Ḥūarte d’Apamène (Syrie)’, Travaux et Mémoires, 7 (1979), Centre de Recerche d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance, p. 352, note 4.

Pauline Donceel-Voûte, Les pavements des églises byzantines de Syrie et du Liban. Décor, archéologie et liturgie, Publications d’Archéologie et d’Histoire de l’Art de l’Université Catholique de Louvain, 69 (1988), p. 467, fig. 446.

H. W. Pleket and R. S. Stroud (eds.), Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum, vol. 40 (Amsterdam, 1990), p. 550, no. 1773.

Jean Bingen, ‘Sur quelques Mosaïques Inscrites d’Apamène’, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 95 (1993), p. 123.

Denis Feissel, ‘L’épigraphie des mosaïques d’églises en Syrie et au Liban’, Antiquité tardive, 2 (1994), p. 288.

Jean-Paul Rey-Coquais, ‘Mosaïques inscrites paléochrétiennes de la Syrie du Nord-Ouest’, Syria, 73:1/4 (1996), p. 105, Inscription no. 2 ter.

Ancient Sculpture and Works of Art, Sotheby’s, London, 7 December 2021, Lot 29

With Asfar Bros., Hotel St. George, Beirut, from at least 1968, recorded there by Henri Seyrig in 1968.

Private Collection of Antonin Besse (1927-2016) and Christiane Besse (1928-2021), Beirut and Paris, acquired from the above and shipped to France in January 1970, accompanied by an invoice dated 23 January 1970, and shipping documents.

Sold at: Ancient Sculpture and Works of Art, Sotheby’s, London, 7 December 2021, Lot 29.

Private Collection, Malibu, California, acquired from the above.

ALR: S00241621, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

The Besse family collection started with Antonin ‘Tony’ Bernard Besse’s father, Sir Antonin Besse (1877-1951), who began acquiring objects in the early 20th century. Many items from Sir Antonin’s collection are now in the British Museum. Besse built his wealth through the company he founded in Aden, A. Besse & Co., which served as an agent for many international insurance, airline, and shipping companies. He also worked as the agent of Royal Dutch Shell. Besse brought great energy and drive to his business, as captured by Evelyn Waugh in the character of Monsieur le Blanc in Scoop. In 1949, Besse donated funds to the University of Oxford for St Antony’s College, requesting that it welcome foreign students, with no test of political, racial, or religious beliefs to determine entry. His hardworking ethos and his passion for education were passed down to his son Tony.

Tony and his sister grew up in occupied France, raised by their English nanny after their parents escaped to Aden in 1941. Tony began running errands for the Resistance, including stealing German weapons and equipment, and awaiting covert supply drops from Allied aircraft. This was a risky endeavour: once, his sister had to sit on a stolen German gun to hide it while his house was searched, and on another occasion, Tony was captured by an Italian officer, who let him run due to his youth and the fact the officer had known Tony’s father in Somalia. Tony was even expelled from school for standing up and shouting at the Headmaster, who was a supporter of the Vichy regime. After the war, Tony began working for the family business but found he was unsuited to the comforts of office life. He soon left to New York, where he made his living as a taxi driver. After his father’s death in 1951, Tony returned to Aden and took over A. Besse & Co.. Here he met Christiane, who was working as a journalist in Yemen at the time. They married in 1957.

During this period, the couple expanded their antiquities collection. Tony would frequently dive with Jacques Cousteau in the early days of sub-aqua, and gather Greek and Roman treasures off the Turkish coast. Antonin Louis and Joy-Isabella attribute a large part of the success of their parent’s collecting endeavours to Christiane’s erudition and uncanny foresight. After her death, they discovered that she had procured export certificates from the government in Aden in the early 1960s – a level of documentation that was highly unusual for this time. These documents saved the collection during the events of the Aden Emergency, and the children and the collection found safe harbour in Europe. Tony and Christiane moved to Beirut, where they continued to follow their passion for antiquities. They collected diversely, acquiring alabaster bulls and busts alongside delicate Roman glass, small bronze animals, marble statues of goddesses, and Byzantine mosaics. When the civil war began in Lebanon in 1975, the couple left the Middle East and ceased adding new items to their collection.

Tony is also remembered for his philanthropic activity, including donating the funds for the purchase of St Donat’s castle and estate for Atlantic College in 1960. He served as the founding chair of the International Board of United World Colleges, and worked closely with them throughout his life. Christiane started a new career as a literary translator in the 1980s, and worked with authors such as James Baldwin, William Boyd, William Shawcross, Amitav Ghosh, and Maya Angelou. She went on to establish her own publishing company in Paris, Editions Philippe Rey.

Enquire

Enquire